Trump’s Tariffs Could Decimate Asia’s Smallest Economies and Weaken U.S. Influence

In the shadow of Washington’s trade war with Beijing, unchallenged U.S. tariff rates could have ruinous effects on the economies of Southeast Asia’s poorest states.

By experts and staff

- Published

Experts

![]() By Joshua KurlantzickSenior Fellow for Southeast Asia and South Asia

By Joshua KurlantzickSenior Fellow for Southeast Asia and South Asia

By

- Annabel RichterResearch Associate, Southeast Asia and South Asia

In recent weeks, White House economic policy has focused on making deals, keeping truces, or in some cases—like that of Brazil, which President Trump himself seems personally aggrieved at—levying harsh punishments on the world’s biggest economies.

For instance, although details remain sketchy and vague, the White House has announced a trade deal with Japan in which the world’s third-largest economy would face either 15 percent or 26.4 percent tariffs, depending on which side you believe. In addition, the White House has claimed that Japan will invest $550 billion in the U.S., claiming at one point that these funds would be controlled by President Trump himself. (Japan disputes that such an investment will be set up at all.) Meanwhile, Trump gave a recent announcement that any final decision between Washington and Beijing on tariff rates on Chinese goods would be delayed—yet again—for a period of 90 days, an extension of the two superpowers’ trade truce. And the White House has seemingly established at least the outlines of a trade deal with the European Union, though any final and formal agreement seems far off.

This focus on interactions with economic giants and media coverage of big deals (as well as other major stories, including the deployment of the National Guard to Washington D.C.) has overshadowed another aspect of Trump’s tariffs—that high remaining tariffs on some of the poorest countries in Asia (and other parts of the world like Africa), often with no clear reason, have the potential to completely ruin the economies of these already-impoverished states, most of which have no ability to buy more goods from the United States anyway.

On August 7, for instance, tariffs ranging from ten to forty percent kicked in for some of the poorest states in Southeast Asia and Oceania, affecting Laos, Myanmar, Nauru, Papua New Guinea, and Timor-Leste, among others. (Cambodia, another of the region’s poorest states, barely averted higher tariffs by signing a last minute deal agreeing to 19 percent tariffs on exports to the United States.)

Laos is emblematic of the problem. Laos, which has a per capita GDP of around $2,100 and is considered one of the least developed countries in the world (though that designation may be lifted next year), was hit with a U.S. tariff rate of 40 percent. The United States has a modest trade deficit with Laos, but nothing compared to the deficits it has with countries like Vietnam, Japan, or Mexico. Last year, America’s trade deficit with Laos was around $760 million. (For comparison, the U.S. trade deficit with Vietnam last year was $123.5 billion.) The U.S. last year exported some rice, industrial machinery, plastic goods, and other items to Laos; Laos exported some garments, textiles, and a range of low-value commodities including coffee, wood, and rubber. There are very few sizable companies in Laos, or wealthy individuals who could afford the United States’ higher-end consumer goods; it is hard to imagine what else Laos could purchase.

And while the United States is not among the top five of Laos’ two-way trading partners, it is among its biggest export markets. Given that Laos primarily produces low-value commodities that can be procured elsewhere, a forty percent tariff will be ruinous to many parts of Laos’ economy. The BBC reported that the tariffs could impact 60,000 jobs in Laos’ commodities and garment sectors, some of the only sectors that provide income greater than subsistence farming. And for what end? Laos may turn even more to China as a trading partner, reducing the minimal influence the U.S. has in Laos now. A quarter of the people in Laos live in poverty; though this figure represents a decrease from over thirty percent a decade ago, this economic disruption could increase poverty and hunger across the nation again as well.

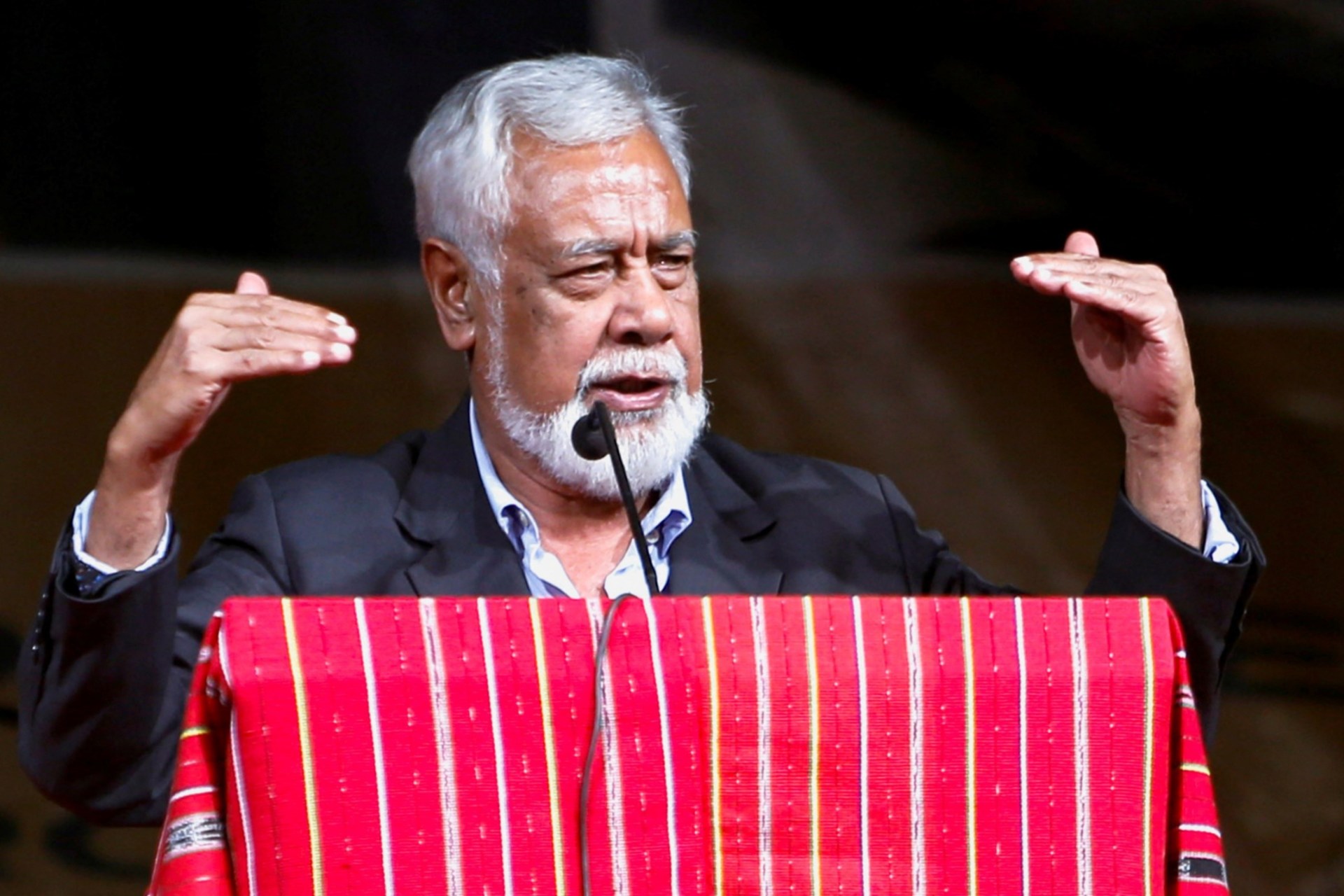

Unlike some of its neighbors, Timor-Leste—Asia’s youngest nation and the poorest state in Southeast Asia—has not had to wrestle with tit-for-tat increases in rates since Washington’s imposition of a baseline tariff of ten percent against the country’s exports in April. However, with a GDP per capita of roughly $1,300 and a 42 percent share of its population living in poverty, even this comparatively low rate could send serious shockwaves through Timor-Leste’s very weak economy. Data from the Asian Development Bank indicates that thirty-eight percent of Timor-Leste’s 1.3 million-strong populace depend on the cultivation of coffee for their livelihood, and coffee constitutes the country’s largest non-oil export. Of its total exports to the United States, valued at $4.73 million USD in 2023, Timorese coffee alone comprises more than eighty-five percent. (Starbucks has long supported Timorese coffee growing and has been a major buyer of Timorese coffee.)

Although the United States is not Timor-Leste’s top trading partner, it still accounts for a significant percentage of the country’s non-oil exported goods. At the same time, the U.S. enjoys a trade surplus with the tiny country. Experts from the region have already raised concerns about U.S. tariffs undermining the competitiveness of Timor-Leste’s limited specialized exports. Combined with its fragility in the face of a withering dollar and the withdrawal of American foreign aid, the Timorese economy is especially vulnerable at the moment, and any sizable decrease in exports could make Southeast Asia’s poorest country—which has already tilted toward China—far poorer.

Like Timor-Leste, Papua New Guinea’s trade profile depends largely on the exportation of petroleum and minerals, as well as a variety of different agricultural products. PNG is even poorer than Timor-Leste and Laos; in one comprehensive study, the World Bank found that nearly 75 percent of its population lived in poverty, among the worst figure in the world. President Trump has announced a 15% tariff on Papua New Guinean exports. PNG had already pledged not to retaliate in the face of the baseline rate initially announced in April: Prime Minister James Marape affirmed that the country would not institute counter tariffs in the hopes of remaining committed to “free and fair trade.” Yet with the tariffs implemented, PNG may further shift trade toward China and other regional partners and limit PNG’s ability to deepen economic ties with America.

The tariffs could have an impact on strategic U.S. links with PNG, which sits in a geographically important position between Southeast Asia and Oceania. Papua New Guinea’s ties with the United States deepened with the signing of a defense cooperation agreement in May 2023, but may now be threatened by the tariffs, as well as China’s massive efforts to woo the country.

Other poor countries face similar situations. As a state in the midst of a civil war, Myanmar is a unique story, with the state still technically run by a brutal junta. Washington has not imposed tariffs on Naypyitaw in the past, even while limiting U.S. investment and punishing Burmese oil exports. Why now hit Myanmar with a 40 percent tariff, while the country’s economy is in freefall?

The questions go on. Why does Nauru, a tiny island in the Pacific, face tariffs of 15 percent (albeit down from initially proposed tariffs of 30 percent)? Why does Fiji, another poor Pacific Island state, face tariffs of 15 percent (again, down from an original proposal of 32 percent?) As Fijian Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Trade Manoa Kamikamica told Radio New Zealand, Fiji accounts for less than 0.0001 percent of total US imports, “posing no discernible threat to US industry.” Again, these islands are important strategically, and China has continued to aggressively court them too. With little recourse available to Southeast Asia’s poorest states, the tariffs risk not only devastating economies but also costing the U.S. strategic influence in the region.